October 7, 1987 Guy Klucevsek: "Polka from the Fringe" at the Revival Club

From Joseph Franklin’s memoir, Settling Scores

http://www.josephfranklin.org/?page_id=21

David-Michael Kenney whispered to Guy Klucevsek as he ushered him back on stage to a raucous standing ovation at a downtown Philadelphia night club, "Better get an agent." Guy looked at him, puzzled and asked, "An agent, why?" "Cause you have a hit on your hands," David told him, smiling. Startled at the suggestion but smiling back confidently, Guy shook his head, as if he hadn't realized what had just happened.

Before moving to Brooklyn and eventually Staten Island, Guy Klucevsek spent several years living in southern New Jersey not far from downtown Philadelphia. During those years he performed with the Philadelphia Composers' Forum as a guest before joining the Relâche Ensemble a year or so after it was formed. Guy remained with Relâche for the next 10 years as he simultaneously pursued a downtown New York presence and distinctive solo performance, recording and composing career. During his tenure with Relâche he was one of the ensemble leaders. Everyone in the ensemble

respected his acute musical sensitivities and easy-going disposition. He composed innovative works for the ensemble, earning a role as one of the group's more productive composers. Over the years his back-and-forth visits from New York to Philadelphia for rehearsals and concerts forged a close, enduring friendship between us.

When New Music America '87 was taking shape I wanted Guy to have a special role, both as a performer and composer. A year or so before the festival Guy called to tell me about a project he had just launched, one he was going to name "Polka From the Fringe".

Growing up as a member of a Slovenian family in Western Pennsylvania's coal-mining country in the late 1950s, Guy was influenced by the music of Frankie Yankovic and other local polka bands and accordionists. In high school he formed his own polka band playing polkas he transcribed from radio broadcasts at weddings, parties and clubs, eventually writing several. After entering college, polkas lost their identity for Guy as he tenaciously pursued "serious" composition studies while developing a repertoire for the accordion that would earn respect - for the instrument and himself - from jaded faculty and students. His self-induced lapse of listening to, and playing, polka music lasted until 1980 when he discovered the Tex-Mex music of

233

Flaco Jiminez and the Louisiana Cajun musician Nathan Abshire.

Each of these musical genres are, interestingly, rooted in polka forms and have earned a loyal following among constituent populations as well as scholarly respect for their important folkloric contribution to American "roots music". The more he listened to these and other polka music styles, the more seriously Guy began to re-discover or re-explore the polka. In 1986 he invited a group of composer-friends to, essentially, put all inhibitions aside and write a polka for him, preferably for solo accordion or accordion with tape or accordion with simple, easy-to-create accessories or props. "Re-think the polka. What is a polka? What do you listen for in a polka?"

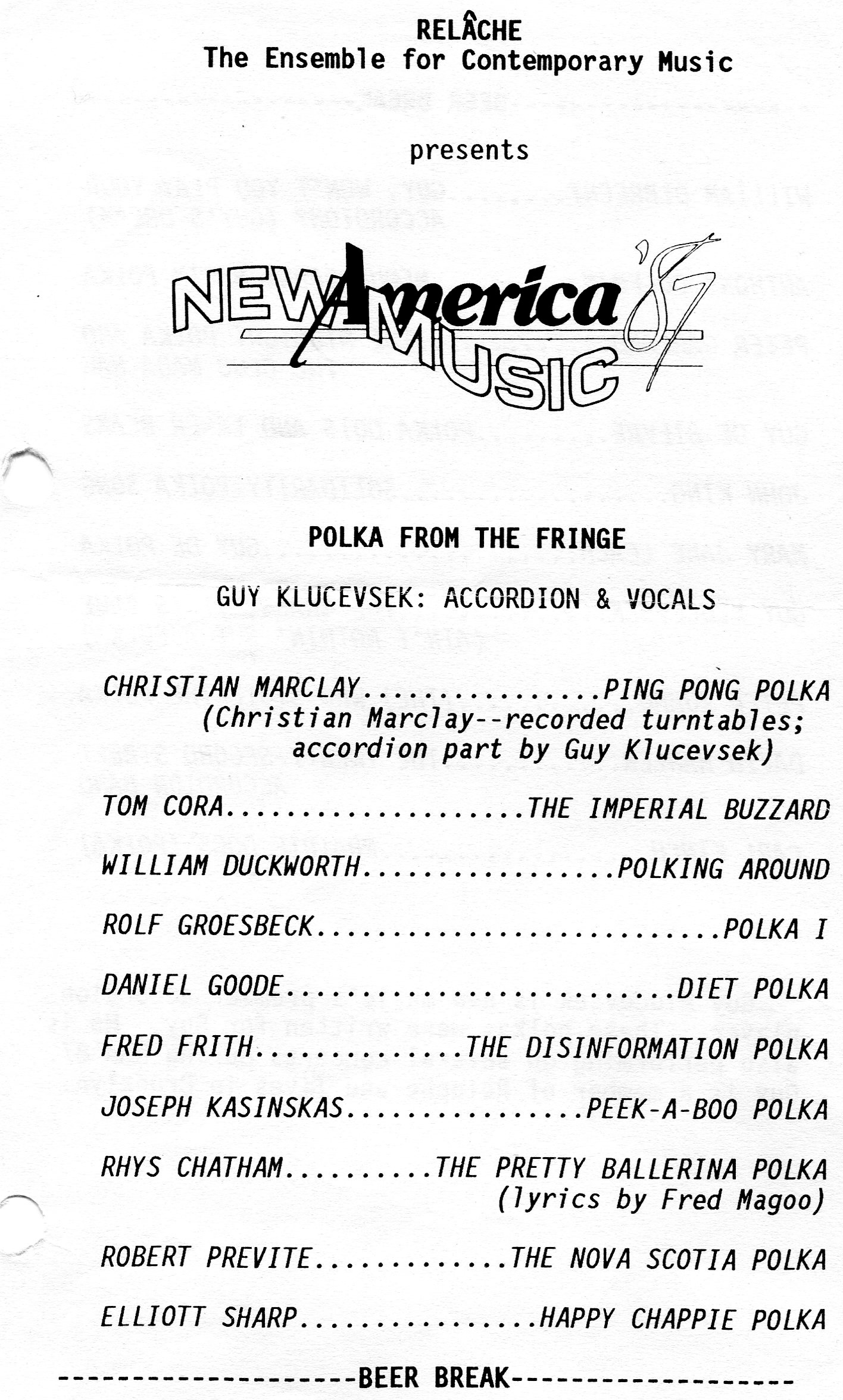

These are several of the challenges he gave to the composers. The result: 32 different polkas, all initially three minutes long, from a variety of composers as widely divergent as one can imagine. From William Duckworth to Lois V Vierk, from Fred Frith to Aaron J. Kernis, the polkas covered a genre-bending array of musical madness and elegance. Polka From The Fringe received its world premiere at the festival.

Rather than simulate a club environment for the performance we scheduled it for a trendy, respectably seedy after-hours dance club in Old City Philadelphia named "Revival", long-since gone, a casualty to the gentrification and galleryfrication of that historic section east of center-city near the Delaware River waterfront. At that time Revival attracted a mixed crowd of emerging and seasoned artists, and art students, along with the usual sub-urban-bound wannabes and curiosity seekers. We had hoped that by placing Polka From The Fringe in Revival and promoting it as a "downtown New York" event, we would draw not only the visiting festival attendees but the local crowd as well. To this day I'm not certain who was there or from where they came but it was packed, wall-to-wall with folks looking for a good party. Guy did not disappoint.

Thirty-two polkas - performed in two 45-minute sets, one more outrageous, or touching, than the previous, performed in a manner Guy never before revealed to his friends - was one of the true highlights of New Music America '87. His singing the lyrics to David Mahler's The Twenty-Second Street Accordion Band after he had ripped off his starched white shirt and folded it in pleated sections to "play" it is a sight that I don't think any of us in attendance that night will ever forget. It was Guy's night and as memorable a New Music America event as any during the festival's 11-year history.

Polka From The Fringe has been one of Guy's more successful projects.

234

Following the premiere performance and subsequent solo concerts elsewhere he arranged the polkas for a group of friends and musicians based in New York who became the "Ain't Nothing But A Polka Band." They toured throughout the United States, Europe and Japan over the next couple of years and recorded 28 of the polkas for "eva records," then based in Tokyo. Guy never did look for an agent.

235

For most of the performance of Polka From The Fringe I stood at the bar surrounded by a group of large guys from Montana who took turns pouring shots of whiskey for me to drink. Essentially, it was a test to see if I could keep up with them. This was a problem since I cannot stand the taste of straight whiskey and never developed the rhythm of drinking shots of anything alcoholic as a means of bonding with my macho friends. I prefer sipping a good dark stout or Cuba Libre when out and about. At all other times I rely on wines to temper my meals and lighten my moods. These guys were insistent and a bit annoying since I was hooked up to David-Michael Kenney's communications system so I could be in touch with him and others in the production crew at anytime during the festival.

Fortunately there were no emergencies that night, mainly because Polka From The Fringe was the only thing happening.

♪

POLKA FROM THE FRINGE

Earlier this year, Joseph Franklin, Joe Kasinskas and Arthur Sabatini reunited with Guy Klucevsek to produce this edition of the ongoing series The Relâche Chronicles.

https://www.relache.org/podcast/episode/7a58a26b/episode-ten-guy-klucevseks-polka-from-the-fringe

I have been so busy with these posts, and this is so fresh (it hatched on September 19) but I will transcribe it for a future post, which gives me a chance to revisit the Polka Fringe once more. Meanwhile, this is what I’m talking about, with emphasis on the beer breaks.

Augusta LaPaix and Guy Klucevsek during the festival, for a nation-wide radio program from the service of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. (Ignore that stuff at the end that I haven’t had a chance to edit out.)

And before we get to the live link, there is all this and a book and more with the Starkland recording of the works, available in normal and digital formats, (on Bandcamp which is still alive for now despite having been redigested again this week). These are the members of the “Ain’t Nothing But A Polka Band” ensemble.

https://starkland.org/catalog/st218/ for the normal formats

Bandcamp tool here:

Finally, POLKA FROM THE FRINGE, LIVE IN PHILADELPHIA!

And most, if not all of the actual Philadelphia performance is here, provided by Relâche through the OtherMinds archive:

https://archive.org/details/NMA_1987_10_07_2_c1

described as:

The Festival’s tenth concert was devoted entirely to polkas; all performed by the lively composer/accordionist Guy Klucevsek. Klucevsek, also a member of Relâche at the time, performs his entire, now cult album, Polka From the Fringe. Polka From the Fringe was a series of commissions started in 1986 where Klucevsek “invited the most improbable composers to put all inhibitions aside and have a go at the polka form.”

Polka From the Fringe was originally released on cassette and then on CD but was out of print for nearly twenty years before Starkland Records reissued it as a special edition double CD in 2012.

Notes from the concert program: “This evening of polkas, pseudo-polkas, and decimated polkas is a tribute to the most notable dance form ever concocted.”

Polka From The Fringe is two 45 minute sets of nuclear polkas, featuring over 30 three minute commissions from the following composers: Thomas Albert, Mary Ellen Childs, Anthony Coleman, Nicolas Collins, Tom Cora, Alvin Curran, Paul Dresher, William Duckworth, Carl Finch, Fred Frith, David Garland, Peter Garland, Daniel Goode, Rolf Groesbeck, William Hellermann, Robin Holcomb, Wayne Horvitz, Jerry Hunt, Scott Johnson, Joseph Kasinskas, Aaron Kernis, Guy Klucevsek, Mary Jean Leach, David Mahler, Christian Marclay, Robert Moran, William Olbrecht, Zeena Parkins, Bobby Previte, Elliott Sharp, Lois V Vierk, David Weinstein. This concert was held at Revival, on October 7, 1987

*

Review of the album by Frank Oteri, reproduced below the link:

https://newmusicusa.org/nmbx/polkas-from-the-fringe/

Sounds Heard: Guy Klucevsek—Polka from the Fringe

Guy Klucevsek’s Polka from the Fringe is another one of these projects and is much in the same spirit, albeit with a few twists. Between 1986 and 1988, Klucevsek commissioned a bunch of composers to write polkas for another keyboard instrument, the accordion. While for most people in this country the accordion primarily conjures up oom-pah bands at old beer halls, generations ago it also inspired compositions by Henry Cowell, Paul Creston, and Alan Hovhaness. In Europe the instrument is now regularly used in cutting-edge new music. (There’s actually a substantive list of European avant-garde compositions for solo accordion and orchestra!) But here in the United States there have only been a handful of accordionists who have attempted to explore a broader range of possibilities, though admittedly Pauline Oliveros as well as William Schimmel and Klucevsek—both through their own compositions and commissioning work from others—have done a lot to recontextualize the instrument. Polka from the Fringe, however, is an attempt to get composers to directly engage in the squeezebox’s more quotidian roots.

Selections from the repertoire Klucevsek engendered were originally released on cassette in the late ‘80s and then on two different CDs in the early ‘90s on now-defunct labels. Starkland’s new 2-CD release of Polka from the Fringe has finally made this material available once again and collects it for the first time in one place. All in all, the discs contain a total of 29 tracks written by Klucevsek and 27 other composers. While neither Babbitt or Cage is represented (too bad), the range here is as broad as the Waltz and Tango projects and perhaps somewhat more so since the resulting pieces not only include solo accordion compositions but also pieces for a full polka band (the band’s name is Ain’t Nothin’ But A Polka Band) in which Klucevsek is joined by David Garland singing and whistling, John King on guitar, violin, dobro, and vocals, David Hostra on a variety of basses from stand up to electric to tuba, and Bill Royle on drums, marimba, and triangle, as well as other occasional guest musicians such as violinist Mary Rowell and percussionist Bobby Previte.

The music turns on a dime from track to track. The sheer loveliness of William Duckworth’s Polking Around or Mary Jane Leach’s Guy De Polka conjures up a very different mood from the spikiness of pieces like Aaron Jay Kernis’s Phantom Polka and Mary Ellen Childs’s Oa Poa Polka. I couldn’t get enough of the relentless experimentalism of Daniel Goode’s Diet Polka (a personal favorite), but Peter Garland’s pastoral Club Nada Polka, which immediately follows it on the CD, was nevertheless a fascinating juxtaposition. Many of the composers used the polka as a springboard for out and out zaniness, such as Fred Frith’s The Disinformation Polka, Lois V Vierk’s Attack Cat Polka, or Pontius Pilate Polka by Microscoptic Septet leader Phillip Johnston. Then there’s Elliott Sharp’s Happy Chappie Polka, a visceral minute and a half of punk assaultiveness that should forever put an end to the mistaken belief that polkas are milquetoast. It’s a 1979 piece which predates Klucevsek’s commissions, but it is a very welcome inclusion nevertheless.

In the very extensive booklet packaged with the discs, which includes the complete lyrics for all the tracks featuring vocals (try to sing along), there are informative essays about the genesis of the project by Klucevsek as well as Elliott Sharp. In his essay, Sharp says that he and Klucevsek both found inspiration in a dismissive comment made by Charles Mingus: “Let the white man develop the polka.” I would have loved to have heard what Mingus might have done with polkas. (A Mingus album released only a year before his death completely redefined the Colombian cumbia.) Perhaps an even broader range of adventurous creative musicians will be tempted to tackle the polka after hearing what Klucevsek and his compatriots did with it now more than 20 years ago. Perhaps, better still, the next time someone comes up to you claiming to be able to define new music, tell him or her to listen to these recordings.

*

Kyle Gann, “Music Notes: Guy Klucevsek Plays Polkas for Weird People”, I presume for the Village Voice, on Guy coming to New York City with his Ain’t Nothing But A Polka Band band to play polkas in 1989, full text reproduced below the link:

https://www.kylegann.com/CR-Klucevsek.html

Accordionist Guy Klucevsek intones one caveat for those tempted to come to his concerts. "Remember," he cautions, "this isn't weird music for polka people, these are polkas for weird people."

Klucevsek--to pronounce his name, say the "c" as an "s," and leave out the "s"--doesn't look like a weird person as he explains the wrinkle he's created in the history of the humble polka. Onstage, however, his shy, Clark Kent demeanor gives way to a canny self-effacing showmanship that has charmed audiences on the east coast and across Europe. The man who single-handedly made the accordion a staple of downtown Manhattan new-music ensembles, Klucevsek is arguably the world's greatest virtuoso in the instrument's growing avant-garde repertoire. He's also the instigator of a collection of new polkas, which he calls "Polka From the Fringe," 31 certifiably weird pieces, of which 25 will be performed in their Chicago premiere Monday.

The light bulb that eventually resulted in "Polka From the Fringe" popped on over Klucevsek's head in 1986, while listening to pianist Yvar Mikhashoff's tango collection. Klucevsek began asking his composer friends--Bobby Previte, Christian Marclay, Lois V. Vierk, David Garland, Nicolas Collins--to write "Polkas" for him, imposing only two criteria: that the piece be limited to three minutes and that it be playable in both solo accordion and quartet versions. Given such vague directives, his friends responded with a wild variety of firsts: the first 12-tone polka, the first polka in 7/8 meter, the first polka with manipulated-turntable solo, the first computer-assisted polka, the first deconstructionist polka, and my favorite--the only polka ever written that requires the band to take off their shirts and perform on Kleenex boxes. Five or six of the polkas, he says, "you could drop into a dance setting and maybe only raise one eyebrow. The rest would stop everyone dead in their tracks."

Klucevsek is one of the few avant-garde musicians who know what a polka is, and he's spent a lot of time defining it. "Traditionally it's a two-step in major key, which is why it has a feeling of good times. As soon as you put it in minor, it comes off more like an Israeli hora. In Slovenian polkas, which is what I grew up playing, it was always an AABBA form, repeated as many times as the dance required. Of course, even as a kid I could hear a huge difference between Slovenian and Polish polkas, and the Tex-Mex polka is very different."

Klucevsek came to the polka early and honestly. Born near Pittsburgh into a Slovenian family, he grew up playing accordion at picnics and weddings, though his teacher also gave him a broad base in classical accordion arrangements. "I was playing Brahms's Violin Concerto, the Tchaikovsky First Piano Concerto, Bach inventions, Scarlatti sonatas on the accordion. I can't say it was always in the best taste, but it gave me chops. The Brahms was pretty wild." Entering music school at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Klucevsek disowned Slovenian music for fear he would lose credibility. "It was bad enough I was playing accordion."

Later, at the University of Pittsburgh, Klucevsek met one of the pioneers of electronic music, Morton Subotnick, who played for him Steve Reich's Come Out and Terry Riley's Rainbow in Curved Air, pieces that convinced him to become a serious composer. He followed Subotnick to the California Institute of the Arts, and after working in the electronic studio there he realized that new-music technology was making his instrument more relevant. "Working with electronic music, where you can sustain a sound indefinitely, got me thinking about the sustaining possibilities of the accordion. And on the synthesizer, you couldn't just play pitches, you had to decide on the color first, whether it was a sine wave, saw-tooth, square wave, or whatever. I started associating those with the switches on the accordion, which is such an acoustically rich instrument, but I had never heard it that way before."

Klucevsek concertized and taught in Philadelphia and New York for more than a decade without gaining much attention; he can count the events, all since 1984, that have marked a change in the public attitude toward the accordion. "The single biggest change was Paul Simon's album Graceland, which used South African, Cajun, and zydeco players." Simon, he says, started a return to regional American music. Klucevsek had learned of the rich American regional accordion tradition in 1980: "I had been to the New Orleans Jazz and Blues Festival and heard 20 accordion players there who blew my socks off." He also mentions Ry Cooder, who started using Flaco Jimenez in his sound tracks, Clifton Chenier, Buckwheat Zydeco, Los Lobos, and Tom Waits as influences. Then there was the success of Tango Argentina on Broadway, because although Astor Piazzolla had been selling out halls in Europe since the early 70s, he wasn't known at all in the United States.

"Someone asked me in an interview five years ago, 'What could turn the accordion around?' And I said, 'If somebody introduced it into the mainstream, so that people who don't have any contact with it outside of polkas, who see it as a corny instrument, would listen to it in other contexts, too.' And I think that's what happened."

Most of Klucevsek's performances have been in arty contexts where he's spent more time explaining the polka than defending his deviations from it, but occasionally he'll find himself deep in polka country, meeting resistance. He spent February at a performing residency in Iowa, and he says, "I'd ask for questions and people would say, 'I'm Slovenian, and you can't dance to these! I'd answer, 'Well, you know how Chopin wrote mazurkas and waltzes, and Bach wrote gigues and minuets, and you can't dance to them; they were using them as compositional forms.' 'Yeah, but you can't really dance to it.' Even intellectuals will give me that line sometimes, I think because there's an aura about the polka that it's a good-time thing, you shouldn't intellectualize it. On a pop level, it's sacrosanct.

"I try to explain to people who dance to polkas that by creating an alternative collection I'm not trying to negate what's already there, I'm trying to add to it in a different way. But some people see it as a rejection of the traditional form. I'm working in the only language of polka I can work in, my compositional style and my performing style. I couldn't be a traditional polka player at this point."