October 3, 1987 NMA Philadelphia day 2/10

Marcel Duchamp, RoseLee Goldberg, Marc-André Hamelin, Charles Forbes, Laurel Wyckoff, Relâche, Aaron Kernis, William Duckworth, George Russell and the Living Time Orchestra with audio links

New Music America 1987 Philadelphia, Day 2

Marcel Duchamp, Centenary Lecture

RoseLee Goldberg, "New Music and the History of Performance"

Marc-André Hamelin - Charles Forbes - Laurel Wickoff

Aaron Kernis: Music for Trio Cycle 4 Part 1

Relâche - William Duckworth: Music in the Combat Zone

George Russell and the Living Time Orchestra - The African Game

(Alvin Curran’s The Maritime Rites postponed until tomorrow.)

=========================================

Marcel Duchamp, Centenary Lecture:

RoseLee Goldberg, "New Music and the History of Performance"

Author/critic RoseLee Goldberg in her lecture, "New Music and the History of Performance" Sunday morning at the Philadelphia Mseum of Art, aptly reminded her audience that experimental and performance art- still considered avant-garde by many - is far from new.

Her talk focused on the Italian futurist F. T. Marinetti who, as early as 1912, advocated the commingling of performance and graphic arts, and who invented "music machines" before synthesizers were even imagined.

Performance art is, of course, an integral part of this festival, with compositions for video, dancers, and interactive sound: "The Maritime Rites" by Alvin Curran, for ship's horns on the shores of the Delaware River interacting with musicians on barges in the river; and a performance work by Leif Brush using solar-powered FM transmitters.

- Susan L. Pena, Redding Eagle-Times, “New Music Sounds Off in Old Philadelphia”, October 9, 1987

===========================

Marc-André Hamelin - Charles Forbes - Laurel Wickoff

Aaron Kernis: Music for Trio Cycle 4 Part 1

Saturday evening's festival concert at the Port of History Museum proved at least one point: Mixing jazz with other types of concert music is risky. After the vibrant, rockingly good jazz of George Russell and the Living Time Orchestra, the new music by Aaron Jay Kernis and William Duckworth that preceded it seemed pale.

Kernis, a Philadelphia native, and Duckworth, who teaches at Bucknell University, had premieres in the concert's first half that were attractive and sufficiently well-played. ... Kernis' Music for Trio (Cycle IV) had mimimalist tendencies - one of his teachers was John Adams - and a leaning backward towards the colors of late Debussy.

The trio - flute, piano and cello - often merged into a duo-plus-one by playing the same pitch or pattern; this "mirror technique" was interesting to follow. The piece did not seem to have much to say, however, unless it was about atmosphere and technique.

- Lesley Valdes (with contributions by Daniel Webster), "New-music fete floats a concert", Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1987

Actual performance recording: https://archive.org/details/NMA_1987_10_03_c1/C02-01_Trio_Cycle_IV_Aaron_Kernis.wav

==============================================

Actual performance recording:

https://archive.org/details/NMA_1987_10_03_c1/C02-02_Music_in_the_Combat_Zone_William_Duckworth.wav

Duckworth and Goode both demonstrated how the clarity of TMIRM (Turning Minimalism Into Real Music) (come on, weren't you sick of that ugly word postminimal?) allowed for a sharper pointed message than does the diffuse, violent music that is usually considered political.

Duckworth's Music in the Combat Zone infused antiwar texts written/selected by Mindy Winreb with a disarming, cabaret immediacy that might not have survived without Barbara Noska's irresistible theatricalism.

- Kyle Gann, "Quiet Heroics", November 10, 1987, Village Voice

*

Duckworth's Music in the Combat Zone was more literally communicative. It was about war and indivdidual death, and for such a grim title, it was surprisingly catchy, non-ferocious music.

It is scored for a vocalist/narrator, flute, clarinet, saxophones, violin, keyboard, accordion, percussion - in short, for most of the personnel of Relâche. ...

The vocalist, an effective Barbara Noska, sang anti-war poems by Walt Whitman, e.e. cummings and Ezra Pound, and during instrumental interludes, she acted out the stages associated with losing a loved one.

Made accessible by its pop idioms, Music in the Combat Zone was energetic and effective, but not terribly moving.

- Lesley Valdes (with contributions by Daniel Webster), "New-music fete floats a concert", Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1987

=====================================

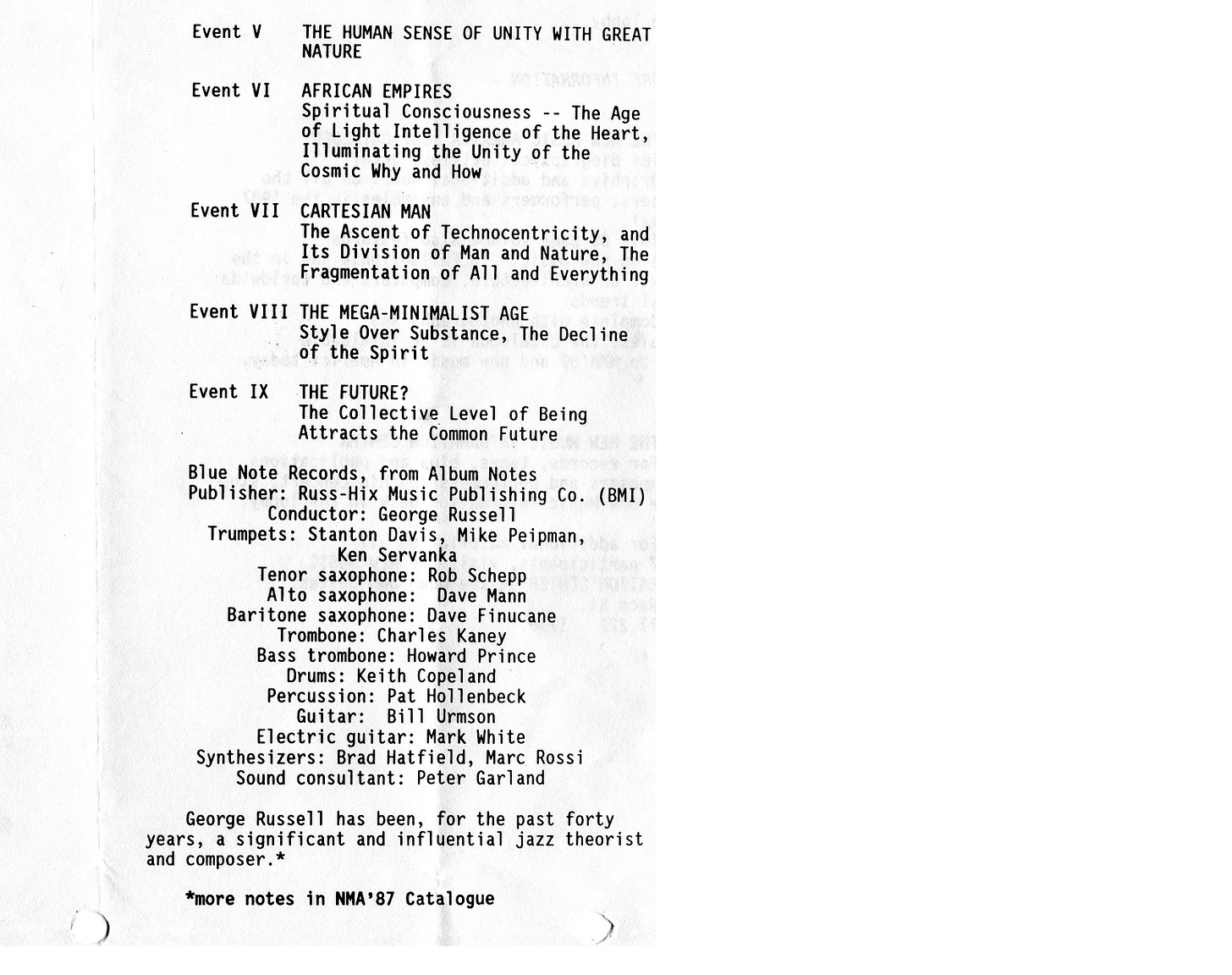

But Russell's 1983 hour-long African Game had more vigor and virtuosity despite an unnecessary, fanciful program describing the beginnings of life to the future. It had another gimmick - it opened with the brass section "playing" battery-powered pencil sharpeners.

- Lesley Valdes (with contributions by Daniel Webster), "New-music fete floats a concert", Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1987

*

Joseph Franklin, from his memoir, Settling Scores

Sometime in mid 1985 or early 1986 I was listening to radio station WRTI-FM late at night. Then WRTI-FM was owned and operated exclusively by Temple University. Their programming format consisted almost exclusively of jazz, with a special Saturday night Salsa show. The student and volunteer disc jockeys were sometimes a bit uneven, raw at times but their presentations were getting better, the result of a new station manager who had been hired with a mandate to smooth things out and provide professional guidance to the student-volunteers. The late night programs tended to play extended works and those which might not fit into a straight-ahead format. It was on one of those shows I first heard George Russell's African

242

Game. It knocked me out! The next day I went out and bought the album and listened to it time and again. Wow!

I had long been a fan of George Russell. Along with other composer-arrangers of big band or large ensemble works like Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn, Gil Evans, Quincy Jones, Sun Ra, Bill Holman, Charles Mingus and Stan Kenton, George's music really caught my ear. He is an important link to the evolution of jazz; active with Dizzy Gillespie in the mid-1940's during the advent of be-bop, then in the mid-1950s when hard-bop and post-bop styles appeared. By then he had developed a mature, sophisticated musical language with adventurous harmonies which swung with the fire and intensity of bop. Like other great composer-arrangers he knew how to draw daring inventive solos from his players, giving them just the right amount of artistic freedom within his elegant formal designs. In 1956 he recorded a landmark album as part of RCA Victor's series "The Jazz Workshop."

This recording, titled "Jazz Workshop: The George Russell Smalltet," is an extraordinary statement with great arrangements of original tunes played by superb soloists and ensemble players. Hearing this recording sometime in the late 1960s gave me insight into the inner workings of a collaborative music ensemble and affirmed - for me - a desire to pursue studies of musical composition.

George eventually settled in Europe where he remained for some years an important figure in the musical cultures there. When he returned to the United States to take a teaching position at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston he continued writing and leading his band with most concert appearances at festivals in Europe. For reasons I have never been able to fully understand, George Russell has never been well known in America. This despite a musical style that's always embraced easily accepted and understood musical constructs like rhythm and song. His music always has a groove, often downright "funky" with easily identifiable tunes. I think even jazz aficionados armed with an educated ear and discerning viewpoint sometimes do not listen carefully to George's music.

There is a tendency perhaps for some to listen too carefully to the musics' inner logic when, in reality, its sophistication resides in the actual groove or song itself. This is partially George's doing since he has created an image for himself as a musical theorist. His ongoing work in this regard, The Lydian-Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, to me doesn't give insight to his music as much as it presents a barrier to it. I feel George's great gift is creating small musical ideas allowing for a variety of interpretations - with the right mix of interpreters - which

243

will yield a larger alluring cohesive musical work. And African Game works for me at this level of audition. I decided upon a second or third hearing that I wanted to program this piece and feature George Russell on the festival.

On the back of the record jacket it mentioned George Russell was managed and booked by Outward Visions in New York City. I called the phone number and talked with a man named Marty Khan who, along with his wife, Helene Cann, is a founding director of Outward Visions. I introduced myself to Marty and asked if we could meet in New York to discuss George's participation on the festival. We scheduled a meeting in the offices of Nikolais-Louis Dance Theatre where Marty and Helene were working to reorganize the company at a time when the Nikolais-Louis Dance Theatre was experiencing severe organizational and financial difficulties. When I learned our meeting would be at the company's office I was stunned.

The Alwin Nikolais-Murray Louis Dance Company had played a critical role in my development as an artist. Years before as an undergraduate at the Philadelphia Musical Academy I studied theatre arts and movement with Ray Broussard, formerly one of the seven original members of the Nikolais Dance Company in 1954. Ray had become a filmmaker and teacher, his methodologies formed from his long association with Nikolais, especially Nikolais' unique use of lighting and costumes to highlight his kinetic fast-paced dance-theatre.

Nikolais composed the music for all of his dance-theatre works using electronic instruments to create sounds on magnetic tape. He purchased one of the original Moog Synthesizers from its creator, Robert Moog, becoming a prolific and innovative composer of "electronic music".

My composition teacher, Andrew Rudin also studied with Robert Moog and was among the Moog Synthesizer's earliest proponents. He was then the director of the electronic music studio at the Philadelphia Musical Academy, one of the reasons I decided to study there. Andrew and Ray grew up together in Beaumont, Texas and remained friends as each of their careers developed in New York and Philadelphia. They correctly concluded that most composers who wrote music for dance and theatre did not have much of an understanding of these disciplines nor did they understand the language of dance and theatre.

Accordingly they created a series of courses designed for composers that would integrate movement, stage design, costume creation, lighting and music as a means to better prepare a composer to work in these media. Their inspiration was Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis,

244

Nikolais' partner and principal dancer. The course was a revelation for me as was discovering the art of Alwin Nikolais and his Dance Theatre.

So here I was poised to meet this guy Marty Khan to discuss how I might engage George Russell, another artist who was an influence on my development, in the Nikolais-Louis office. The "coincidence" was too good to be true.

From our first meeting in the summer of 1986 Marty Khan and I felt an immediate kinship, a trust that mutual interests will yield future projects. He is one of the few people I know who shares many of the same interests and values as I do, who lives a life of an "outcat" [sic] in America, who believes a man's word is good. Sure, the formal arrangements are necessary, but we both knew that an exchange of information and ideas is sealed with a handshake and eye contact that affirms the word. That initial trust we felt at our first meeting has forged a long friendship and resulted in several collaborative projects. And it began with our mutual respect and interest in George Russell and his music.

Marty and I agreed to a fee for George and his Living Time Orchestra to perform African Game at the festival. But given the relatively large number of musicians in the ensemble the fee was a bit too high. To ensure his appearance I asked the Mellon Jazz Festival to help sponsor the concert. During those years the former Mellon Bank sponsored a two-week jazz festival in Philadelphia based on a model presented in large cities throughout the United States. Mellon hired Festival Productions based in New York City to manage the event. I had previously met several of the producers at Festival Productions and felt comfortable approaching them. They too respected George Russell's contributions to jazz and readily agreed to co-sponsor his performance. It was billed simply as "The Mellon Jazz Festival at NMA'87 Presents George Russell."

Scheduled for the second day of the festival, African Game soared. George and his Living Time Orchestra were in great form that night. I felt especially proud that I was responsible for presenting George Russell in a venue with a superb technical crew to help showcase his ensemble and music in a manner befitting someone of his stature. His presence added immeasurably to the overall artistic success of New Music America '87.

First of twelve parts at (all 11 parts flow from it)

https://archive.org/details/NMA_1987_10_03_c1/C02-03_Intro_Cubana_Be_Cubana_Bop_George_Russell.wav

========================================

p.s.

Joseph Franklin’s book about his career in music is available here: