December 7, 1988 Relâche performs James Tenney's "Critical Band" at New Music America Miami

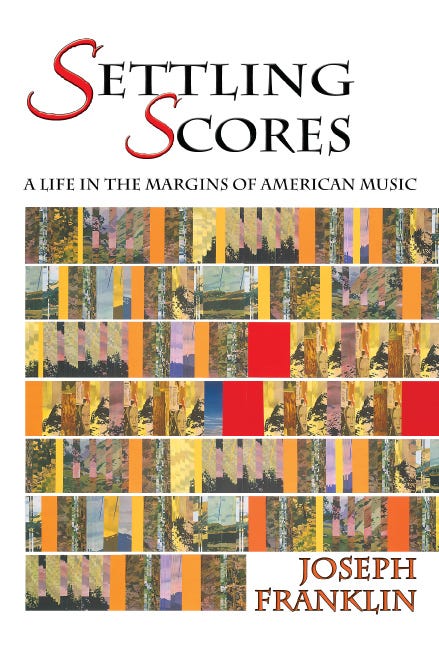

Featuring Joseph Franklin's account of the collaboration from his memoir, "Settling Scores"

Joseph Franklin from his memoir, Settling Scores (see link to book at the end)

====================================================================

The 1988 New Music America Festival was held in Miami, Florida during the pre-Christmas days of December, a time when many performers and New Music enthusiasts from cold cities in North America headed south to warm, tropical, sultry and colorful Miami. One of the concert venues was

246

located on Biscayne Bay directly across from a sprawling mega-shopping mall with stores, boutiques and food stands located throughout the waterfront plaza. An outdoor performance space with a sheltered stage was located at the edge of a pavilion facing away from the glistening waters of the bay.

Standing behind the audience - who were facing the water - was a tall green one-dimensional wooden Christmas tree. At noon each day the wooden Christmas tree would sing. Well, almost.

Positioned from bottom to top on scaffolding attached to the front face of the tree - basses on the bottom, sopranos on the top, of course - a choir sang seasonal songs and Christmas carols for the shoppers who cruised the Mall. But there was a problem. New Music America had scheduled concerts for 1 PM on the outdoor stage each weekday of the festival. The dress and technical rehearsals were scheduled for 11 AM. While the performing musicians from the festival were setting up, checking levels and running through their parts, the Singing Christmas Tree began caroling at noon.

Needless to say this enraged the festival musicians who, in turn, enraged the choir singing from the Singing Christmas Tree. Few people were exhibiting holiday cheer along Biscayne Bay during those days.

Simply no way the Singing Christmas Tree could compete with Scott Johnson's amplified ensemble as they rehearsed sections from his score to the film about Patty Hearst. And The Singing Christmas tree greatly disturbed members of the Relâche Ensemble as they tried to negotiate new works by Stephen Montague and Scott Lindroth, both requiring careful instrumental nuance to support the vocal lines. To add yet more problems for the performers on the ground, in and out of the Christmas tree, overhead large jetliners were taking off including, if memory serves, the daily departure of the Concorde; the sonic thrust from their huge engines shaking everything on the ground below their flight paths directly over Biscayne Bay. Despite these interferences, each of the concerts went off as scheduled but many of the musicians on the festival felt that their music had been placed in a seriously compromised context.

Surely the choir in The Singing Christmas Tree felt equally compromised. Even when the departing jets' engines were not shaking The Singing Christmas Tree to its fey roots, the air around Biscayne Bay was filled with other dissonances. However, a few blocks away at the Gusman Center for the Performing Arts located downtown not too far from Biscayne Bay, a different kind of dissonance was playing itself out. Or perhaps resolving itself.

247

Relâche - along with the Kronos Quartet - was one of the resident ensembles on the festival. Accordingly the group was busy throughout the festival with a variety of rehearsals and performances. Joseph Celli and Mary Luft, festival producers, had received funds from the Pew Charitable Trusts Cultural Program to support Relâche's residency in Miami and commission four new works for Relâche to premiere. Together Joe and I selected Scott Lindroth, Mary Ellen Childs, Stephen Montague and James Tenney to receive the commissions.

With respect to the other three composers - all of them friends and highly esteemed by everyone in Relâche - I was especially eager to have Jim Tenney to write a piece for Relâche. Jim is noe of the most influential and innovative composers in America and both Joe Celli and I were in total agreement that he should have an important role on the festival. In earlier discussions Jim had confided to me he liked the sound of the Relâche Ensemble and had some ideas how he might use that sound to develop a new work challenging the musicians' interpretive skills in unique ways while creating a musical work which continued his exploration of harmonic functionality. Indeed he did. The result is titled Critical Band and to my mind it is one of the finest and most important works Relâche has ever performed and recorded.

Critical Band is, essentially, an experiment in tuning as a means of achieving a pure dominant harmony. The piece is scored for woodwinds, accordion or a drone-like instrument, piano and vibraphone. From the original program notes Jim Tenney explains, "A critical bandwidth is a frequency range within which complex acoustical stimuli evoke auditory responses very different from those evoked by stimuli separated by a larger interval (in the same register). For example, two simple sinusoidal tones separated by an interval much smaller than the critical bandwidth are not heard as two tones at all, but rather as a single tone, with beats which produce a sensation of roughness, at a subjective loudness which is correlated with the sum of their individual amplitudes."

The performance of Critical Band evolves from the normal process of the ensemble's tuning to A-440. Continuing from Jim's program notes, "After establishing a continuous unison on A (its continuity enhanced by a tape-delay system that re-cycles the collected instrumental sounds back into the auditorium), the players begin to expand the range of sounding pitches geometrically, above and below the central pitch. Each successive interval in a given direction is exactly twice the size of the preceding interval in that direction.

248

Although these incremental intervals are always in strict harmonic proportions (i.e., they can be represented by fairly low-integer frequency ratios), they are too small to be recognized as such (or even be heard as intervals) during the first half of the piece, in which the total pitch-range never exceeds the limits of the critical band (which, in this register, extends a major 2nd above and below the mid-point). Only after the expansion process has exceeded the critical bandwidth do the pitch relations begin to be heard as harmonic."

A piece like Critical Band is difficult to realize. Each player must concentrate totally on their roles as they incrementally tune each interval. It requires a somewhat different type of ensemble cooperation: each instrumental part is fiercely intimate yet communal, never losing its identity in the overall structure of the piece. In addition the sonic character of the space that it's being performed in must be highly resonant or it must be electronically enhanced to ensure that the sound appears to float throughout the space.

The success of any performance of Critical Band is incumbent on the sound engineers' abilities to distinguish between the acoustic and electronically enhanced components of the work. Their roles are critical: they must collect the evolving ensemble sound via an analog tape-delay system then carefully mix it with the previously recorded ones to create a seamless sonic tapestry to bathe the auditorium in sound. It's a difficult work fraught with potential problems both physical and structural. But when successfully realized it has a powerful effect as the pure dominant harmony is released from a dissonant texture that has accumulated for some 16 minutes. The climax is almost physical, or metaphysical as the sound virtually explodes throughout the space.

During the final dress rehearsal for Critical Band on the afternoon of its evening premiere just as the first complete run-through ended and the sound slowly faded, I noticed someone standing in the aisle, head down, listening intently to the barely audible decay.

It was John Cage. In the midst of rehearsal hubbub, I had nearly forgotten he was in the auditorium.

John was a featured composer on the festival. A new work of his titled Five Stone Wind was also being premiered that evening; he had just finished the final rehearsal with solo percussionist James Pugliesi before the Relâche Ensemble took the stage. I had greeted him at the end of his dress rehearsal and he asked my permission to listen in on the rehearsal. Needless to say I

249

was honored beyond belief that he would ask my permission to listen in. We were all honored that he wanted to listen and I, of course, invited him to do so. As the sound faded John came over and asked what piece we were playing. "A new work by James Tenney," I answered. "It's titled Critical Band." He smiled and looked up at the ensemble then back at me and said softly, "That is the most beautiful piece of music I have ever heard." I smiled, thanking him, saying "I'll tell Jim."

Jim Tenney and John Cage had been conducting a long correspondence concerning their mutual interpretation or understanding of "harmony"; Jim being an articulate advocate of its architectonic role in musical praxis while John Cage countered that it was an artificial means of organizing primal material and was not a natural consequence of the musical gesture. Following the successful performance of Critical Band, Jim and John renewed their correspondence.

As Jim later told me, smiling as he recalled the moment, John's letter congratulated him ending with the words, "If that's harmony, then I'm all for it." Unable to attend the premiere performance of Critical Band in Miami, James Tenney heard it for the first time in Philadelphia a few months later when Relâche's repertoire until the mid-1990s when several changes in personnel - and instruments - within the core ensemble made a successful realization of the piece difficult.

♪

Some reactions:

...and the only real tonal motion in James Tenney's Critical Band, played by Relâche, is an upward lift to a higher pitch towards the end of the piece.

In a way, one-note works aren't just the next logical step in the great musical strip mine of minimalism, which is still concerned with the weave of rhythms and such basic units of music as arpeggios and riffs.

One note is a world unto itself, without another to create an interval, and thus a tonality or a rhythmic thrust.

- Josef Woodard, Option, March 1989

*

James Tenney's Critical Paths (sic), given its world premiere by the Relâche Ensemble of Philadelphia, turned out to be an arid acoustical experiment in which flute, clarinet, accordion, bassoon, piano and vibraphone sustained an impure A for about 20 minutes. It seemed a pretentious way of saying nothing.

- James Roos, Musical America, "New Music America Festival" May 1989

*

On Wednesday, Relâche performed James Tenney's Critical Band, an essay in tonal relationship and tensions. It began with a unison section that sounded as if the group was tuning and slowly expanded to a slightly greater but still constrained pitch range. Mary Ellen Childs' Parterre, performed by Relache on Thursday, was more rhythmically vital and melodically inspired. Childs relied much on the accordion, making for an especially interesting mix with instruments more usually associated with concert music.

The Relâche idea seems a model of economy and creativity that could inspire similar groups in other cities: Smaller and cheaper and more lively than a traditional orchestra, the ensemble can move fast and loose on musical frontiers and, in the process, carve its own highly creative niche.

- Russell Stamets "New Sounds in a Bazaar Setting" St. Petersburg Times, December 13, 1988

*

A bit more rewarding was Critical Band by James Tenney, performed by the Relache Ensemble — flute, clarinet, sax, bassoon, accordion, vibraphone and deliberately mistuned piano. The work revolves around a single pitch that gradually diffuses, the way a beam of white light might start suggesting other colors as it separates thinly in the distance. The concept was sufficiently novel, the execution remarkably controlled.

- Unsigned review, South Florida Sun-Sentinel, December 9, 1988

*

It seems this is the version by an ensemble named Zeitkratzer; it is the score Tenney created for Relâche, though.

They quote Tenney’s notes in a different video without the score:

A "critical bandwidth" is a frequency range within which complex acoustic stimuli evoke auditory responses very different from those evoked by stimuli separated by a larger interval (in the same register). For example, two simple (sinusoidal) tones separated by an interval much smaller than the critical bandwidth are not heard as two tones at all, but rather as a single tone, with beats which produce a sensation of roughness, at a subjective loudness which is correlated with the sum of their individual amplitudes. Two simple tones separated by an interval larger than the critical bandwidth, on the other hand, are heard as two tones, smooth or "consonant" in quality, and at a loudness which approaches the sum of their (individual) loudnesses (rather than their amplitudes). A performance of this work arises out of the normal process of the ensemble's tuning to A-440. After establishing a continuous unison on this A (the continuity enhanced by a tape-delay system), the players begin to expand the range of sounding pitches "geometrically", above and below the central pitch.

That is, each successive interval in a given direction is twice the size of the preceding interval in that direction. Although these incremental intervals are always in strictly "harmonic" proportions (i.e., they can be represented by fairly low-integer frequency ratios), they are too small to be recognized as such (or even to be heard as "intervals") during the first half of the piece, in which the total pitch-range never exceeds the limits of the critical band (which, in this register, extends a major 2nd above and below the mid-point). Only after the expansion process has exceeded the critical bandwidth do the pitch-relations begin to be heard as "harmonic".'

- James Tenney

♪

Live performance 2019 by Opificio Sonoro Perugia

James Tenney - Critical Band (1988), live recording by Opificio Sonoro Perugia, 14th December 2019 at “Festival Orizzonti”. Coproduced by Opificio Sonoro — Fondazione Perugia Musica Classica — Corsia Of. Opificio Sonoro, variable ensemble: Claudia Giottoli Andrea Biagini Raffaella Palumbo Agnese Maria Balestracci Umberto Aleandri Simone Pappalardo Nicola Cappelletti Laura Mancini Filippo Farinelli Guests: Francesco Dillon Simone Nocchi Conductor - Marco Momi

♪

A version for nine sine waves, but despite short notes, it doesn’t seem to indicate who did it.

Tenney's piece is for 16 or more instruments. This version for 9 sine waves dispenses with the need for so many parts because the sine waves can be extended to the precise durations required. In a live performance with real instruments, the extra players are required to make sure that at least somebody is playing the note the score requires at the correct time. Live performances therefore have much more timbral variety. However, an electronic rendition has the advantage that the pitches can be really precise and create the beating effects that the composer sought. Live performance are also very technically demanding on the musicians. Although the parts are simple, the performers need to be acutely aware of who is playing which note at all times, in order not to risk gaps appearing. This version is also slightly faster than the score, in order to come in under the 15 minute you tube limit.

♪

Performance of James Tenney's Critical Band During the ORCiM Festival 2013 at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, BE. Performed by EM62 (www.modelo62.com), Trio Scordatura (www.trioscordatura.com), Juan Parra Cancino (www.juanparrac.com) and ORCiM researchers (www.orcim.be) on October 4, 2013.

♪

Allmusic description by Jeremy Grimshaw

James Tenney is well-known in academic circles for his groundbreaking work bridging the various fields of music composition, acoustics, and sound cognition. Many of his works tackle a scientific principle or problem, treating it instead as the conceptual foundation for an aesthetic experience. He is perhaps best known in this regard for his pioneering employment of computer tools for both sound production and compositional decision-making, having begun his professional career at the famed Bell Laboratories in the early '60s. A number of his works, however, entrust such acoustical and artistic experimentation to live performers and acoustic instruments. Perhaps the best known of these is Tenney's Critical Band, a work for chamber ensemble of variable instrumentation. Composed in 1988, Critical Band demands from the performers an incredible level of intonational accuracy and consistency in its exploration of the way the human ear responds to sustained sounds.

As is the case with many of Tenney's works, an understanding of the conceptual and sometimes scientific principles behind the composition is very helpful in understanding the musical phenomenon involved. This work takes its title from a term with both physiological and acoustic meaning. Within the human ear there is a long, ribbon of tissue known as the basilar membrane. The membrane is tapered, so that one end is thicker or wider than the other. When a low frequency enters the ear, a particular point near the wider end of the basilar membrane is set into vibration; a higher sound excites a point near the thinner end; the nervous system detects the area on the membrane being excited and translates that into heard pitch. When two frequencies within a certain proximity of each other enter the ear, however, the points on the membrane which they excite overlap, creating a variety of psychoacoustical effects and interference patterns. The "critical band" refers both to the width of a band on the membrane within which these effects occur, as well as the frequency ranges within which multiple sounded pitches can cause such effects. The aim of Tenney's Critical Band is to explore this phenomenon through a musical practice -- in fact, one of the most familiar: the ensemble tune-up on A440 (versions of the piece related to other generative pitches exist as well). The piece centers around a simple tuning A, which is sustained by the player and kept unbroken through the use of a digital or tape delay system. Over the course of the 18-minute work other pitches slowly emerge, diverging from the original A by increasingly larger intervals; the most narrow intervals cause only an undulation of the main perceived pitch, but as the range of frequencies widens all sorts of acoustical by-products, including high, whistling combination tones or humming difference tones, emerge from the composite frequencies. Tenney thus transgresses the boundary between normally discrete pitches, and opens our ears to the surprisingly active universe of sounds that can exist within a seemingly static field of sustained tones.

♪

SF Soundfestival version from 2016:

Tom Bickley, recorder . Diane Grubbe, flute . Kyle Bruckmann, oboe

Phillip Greenlief + Matt Ingalls + John McCowen, clarinets . John Ingle, alto saxophone Tom Dambly + Tom Djll + Theodore Padouvas, trumpets . Brendan Lai-Tong, trombone . Lucie Vítková, accordion . Jason Levis, marimba . Giacomo Fiore, guitar Benjamin Kreith + Erik Ulman, violins . Monica Scott, cello . Scott Walton, contrabass

♪

2013 version by the Indexical Ensemble, of Brooklyn, it would seem:

Martha Cargo, flute; Katie Porter, clarinet; David Kant, saxophone; Tyler Wilcox, saxophone; Anne Guthrie, horn; Thomas Verchot, trumpet; Craig Shepard, trombone; James Rogers, bass trombone; Colleen Thorburn, harp; K.C.M. Walker, piano; Byron Westbrook, synthesizer; John P. Hastings, guitar; Andrew C. Smith, guitar; Ben Richter, accordion; Erik Carlson, violin; Hannah Levinson, viola; James Ilgenfritz, contrabass

♪

from where the long passage at the beginning comes from: